Why Performance Fails Even When Skills Exist

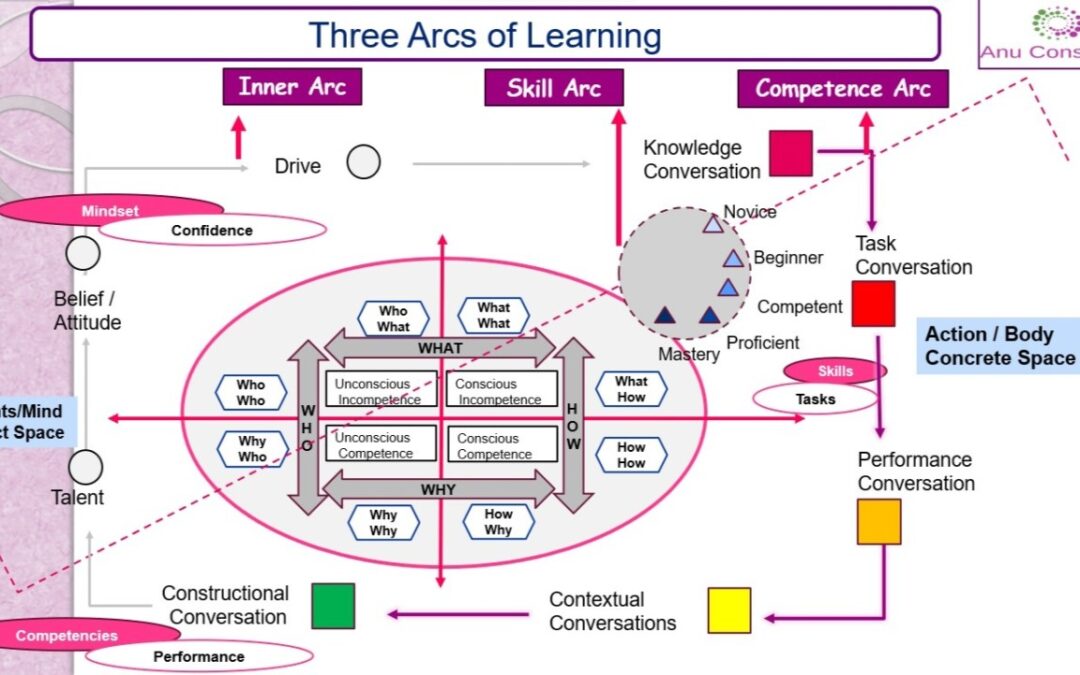

Most organizations spend enormous time, money, and energy trying to improve performance by improving skills. Training programs, certifications, content libraries, workshops, and coaching have become the default solution to every performance problem. Yet leaders repeatedly encounter the same questions: Why does performance vary so widely between people who have the same training? Why do teams improve briefly after a program and then slip? Why do capable people struggle in real situations while those with less technical knowledge excel? The reason is simple: organizations keep optimizing for the Act while ignoring the Actor. What people do is only the visible surface. Who they are, how they think, why they think that way, what drives them, how they interpret situations, and how they integrate experience—all of this lives beneath the surface. This deeper layer is where real performance originates. Every action a person takes is shaped by three arcs: the Inner Arc (values, beliefs, attitudes, identity, meaning), the Skill Arc (task abilities, methods, execution capability), and the Competence Arc (judgment, integration, adaptation, contextual understanding). These arcs operate within different spaces—abstract mind space, concrete action space, and performance/result space—each producing different forms of conversation: knowledge, task, contextual, performance, and constructional. When we understand the arcs, we understand why capability-building fails when done in isolation and why performance strengthens when organizations shape the architecture of the Actor, not just the Act.

The Skill Arc: The Foundation of Doing

The Skill Arc represents what a person can do in a stable environment. It includes task execution, technical ability, procedural knowledge, and the “what–how” combinations that define proficiency. Skill moves a person from novice to beginner to competent to proficient to mastery. Skill is built through repetition, clarity, tools, instruction, and practice. It lives mostly in the “conscious competence” and “unconscious competence” quadrants. Skill conversations happen in the concrete space of action: SOPs, methods, checklists, templates, and procedures. Skill is essential—without it there is no reliable execution—but it is also insufficient. Skill prepares a person for predictable situations. But work today is filled with variability, ambiguity, interdependence, complexity, and constraints. Skill offers methods, not meaning. It offers clarity, not context. It helps you execute tasks well, but it does not help you understand which task is the right task or how much of it is required or what trade-offs must be made. Skill is the “what” and “how” of action. It strengthens performance but does not guarantee judgment. This is why skill-heavy organizations still experience inconsistent performance—they strengthen execution but do not strengthen thinking.

The Competence Arc: The Engine of Judgment

Competence is where skill meets context. It is the integration of knowledge, experience, pattern recognition, interpretation, and decision-making. Competence emerges when people move beyond repeating tasks and begin understanding the meaning behind them—the “why–how,” “what–why,” and “how–how” relationships. Competence is not an individual event; it is a contextual capability built through conversation, feedback, exposure, and reflection. It grows in environments where people are encouraged to explore consequences, understand dependencies, consider risks, and evaluate ripple effects. Competence is 2nd-order thinking—seeing the consequences of consequences, not just the outcome of an action. It is the ability to anticipate second- and third-level effects, sense early signals, interpret variation, make trade-offs, and operate in ambiguity. Competence lives in contextual conversations, constructional conversations, and performance conversations. These conversations convert isolated skills into integrated capability. Training can trigger competence, but only experience, reflection, feedback, challenge, and shared spaces can deepen it. Competence is what allows one person to thrive where another fails, even if both have identical skills. It is the arc that translates ability into adaptability.

The Inner Arc: Identity, Belief, and the Deep Logic of Action

The Inner Arc is the invisible driver of all visible performance. It contains belief, attitude, values, disposition, drive, bias, meaning-making patterns, emotional orientation, and personal identity. It shapes what a person pays attention to, what they avoid, how they interpret events, how they treat others, what they fear, what they accelerate, and what they consider “normal.” This arc lives in the abstract mind space. It shapes the “who–who,” “who–what,” and “why–who” questions that define a person’s relationship with work. The Inner Arc determines whether someone takes ownership or waits for instruction, collaborates or competes, escalates or absorbs, innovates or replicates, asks questions or stays silent. Skill and competence explain the outer layers of performance; the Inner Arc explains the source. Most capability-building efforts fail because they try to change performance without changing the Inner Arc. Performance conversations target behaviour; constructional conversations target competence; but values, beliefs, and identity require deeper conversations—meaning-making, reflection, feedback, psychological safety, lived experiences, role-modelling, and participation in shared spaces. The Inner Arc is where 3rd-order thinking lives—understanding not just the consequences and not just the consequences of consequences, but the system of beliefs, assumptions, incentives, and identity-patterns that generate the consequences. When the Inner Arc shifts, everything downstream—competence, skill, performance—shifts automatically.

What Leaders Must Do to Build the Three Arcs

Leaders today often operate in pressure-filled environments that reward output, speed, and visible action. But organizations that want sustainable excellence must invest in all three arcs with intention. First, leaders must diagnose correctly: Is the issue skill, competence, or Inner Arc? Most performance problems are misdiagnosed as training needs when they are actually issues of context, clarity, judgment, or belief. Second, leaders must shape the enabling environment: Skill grows in clear, structured, tool-rich arenas. Competence grows through exposure, challenge, reflection, and contextual conversations. The Inner Arc grows through meaning, safety, identity alignment, values in action, purposeful conversations, and role models. Third, leaders must strengthen conversations across all spaces: Knowledge conversations build shared understanding. Task conversations improve the skill arc. Contextual conversations deepen competence. Constructional conversations align systems. Performance conversations anchor results. Fourth, leaders must enable upward movement from conscious incompetence to conscious competence across the “what–how–why” grid. Fifth, leaders must operate as architects, not administrators. Skill improves tasks. Competence improves decisions. The Inner Arc improves the whole system. When leaders design the arcs, the system regenerates capability. When they ignore the arcs, performance becomes fragile. In a world where skills change quickly and technology accelerates work, the Inner Arc and Competence Arc will become the true differentiators of performance, leadership, and organizational learning.

This is the shift organizations now need: from training to capability, from behavior to belief, from execution to meaning, from the Act to the Actor. When we understand the three arcs, we understand performance. When we develop the three arcs, we build organizations that are not only skilled but wise, not only competent but conscientious, not only productive but regenerative.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and perspectives—feel free to share them in the comments or write to me. If there are any topics you’d like to explore further, I’m open to suggestions! selfnsystems@gmail.com.